Fig. 1.—

Grave marker for an enslaved girl named Cicely. Photo provided by the

author.

ordinary, save for the fact that it proclaims the youth buried beneath it was the

fifteen-year-old “negro servant to ye Reverend Mr. William Brattle.”

Her tombstone, which faces the oldest university in the United States, is likely the

oldest extant gravestone for an enslaved person in North America.1 Judge Samuel Sewall, a Brattle family friend and

jurist who kept a diary for thirty years, remembered the day of her death as

“exceeding dark at one Time in the morning” so much so that he had

“hardly seen such Thick Darkness. Great Rain, considerable Lightening and

Thunder.”2 But Samuel

made no mention of Cicely’s death or detailed the circumstances surrounding

William Sr.’s decision to erect the tombstone.3 The extant Brattle family papers are likewise silent on

the death of this girl they enslaved. Subsequent generations of historians have

offered only passing acknowledgment of the marker and even less of Cicely.4 In the past two decades much has

been illuminated about enslavement in the Northeast by parsing fragments and reading

documents against the grain. Scholars have painstakingly reconstructed the

narratives of people of African descent and offered a rich tapestry of experience,

uncovering the centrality of enslavement to the project of colonization in the

Northeast. New England’s archives are famously prolific repositories mined

for rendering the lives of Euro-Americans in three dimensions and have spawned our

dominant narratives about religion, trade, geography, and gender. Cicely’s

exceptional but largely unsung memorial illuminates the ways such familiar

constructions remain incomplete.

There is a poverty in the adjectives that we use to describe the lives of early

non-white Americans, but Cicely was vital and real. She felt the cold snow on her

skin every winter and knew the shores of the Charles River. She was a daughter and

an African-descended’ Christian convert in a community of Black people of various

faiths, a New Englander, and a denizen of Cambridge. She was a girl on the cusp of

womanhood with a body going through extreme change. She was a fifteen-year-old

worker who lived and died during an epidemic.

History is a process of commemoration through stories that reflect a scholar’s

own personal lens. Cicely’s story captivated me because the day that I

stumbled upon her both ordinary and extraordinary marker, I was a Black teenager

only four years older than Cicely was at her death. The questions that arose that

windswept fall day in a colonial graveyard inspired me to pursue history and have

continued to shape my intellectual pursuits. Although decades have passed and the

work has taken me thousands of miles away from Cicely, her story continues to burn

within me. The scholarly production of women of color such as Annette Gordon-Reed,

Jennifer Morgan, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Stephanie Jones-Rogers, Thavolia

Glymph, and Jennifer L. Morgan laid the intellectual groundwork for recovering

untold stories such as Cicely’s, offered inspiration to centralize the

narratives of diverse early American women and the power to tell an integrated

history.5 This article is an

integrated microhistory of a slaveholding community that has served to inspire so

many of Early America’s historiographies. As such, it builds upon Wendy

Warren’s work recentering slavery’s centrality to New England, the

expansive Black communities made legible by Gloria Whiting, and the multilayered

world of dependence presented by Jared Ross Hardesty.6 Silence is the common state of the archival record for

most eighteenth-century women, and ever more so for the enslaved. But the frequently

used phrase “little is known about the experience” of enslaved people

during the Colonial Era, privileges the archives as the only repository of

knowledge. Indeed, hanging trees and disappeared neighborhoods linger in the

collective memories of Black and Brown people, whose knowledge has too often been

decried as unhistorical. Even the most prolifically documented cases reinforce

social fictions. I have approached those silences, deaths, and fictions by using the

strategies deployed by scholars such as Marisa Fuentes, Carolyn Steedman, and

Natalie Zemon Davis, whose works problematize the archive and examine them as sites

where patterns of gendered and racialized violence are reinforced. Saidiya

Hartman’s critical fabulation influences my reading of these enslaved

Cambridge women, and I embrace Hartman’s challenge to compose a

“history written with and against the archive.”7

Since the time that Laurel Ulrich penned that iconic aphorism, “Well-behaved

women seldom make history,” scholars have devoted millions of words to

uncovering the lives of women—ordinary and extraordinary, enslaved and

free— exploring and sharpening our understandings of the past. Combining

familiar sources, such as colonial diaries and narratives, with archival and

material culture artifacts, I argue that Cicely’s story, and those of the

enslaved men, women, and children who surrounded her, exposes how historical

structures of race, gender, and status stand at the core of the classic scholarly

narratives that have shaped American history. Cicely’s enslavers were members

of Bernard Bailyn’s cohort of New England merchants and Sacvan

Bercovitch’s puritans. They were counted among Laurel Ulrich’s

“Well-behaved women” and birthed Mary Beth Norton’s Liberty’s Daughters.8 They were the elites whose wealth, generated by

enslaved workers, built the foundations of American society and whose opinions

became codified into law as well as into legends such as the “Protestant work

ethic” and American exceptionalism.9 The lives and labor of people like Cicely lie silently

behind these public legacies.

In the Old Burial Ground, lines of gray slate tombstones sit along winding footpaths,

linking generations in family plots. The Latin-inscribed altar tomb of

Cicely’s enslaver, William Sr., stands among the decorative memorials to

other eminent divines and Harvard presidents. Its weathered stone face bears the

names of Brattle’s wife, Elizabeth; his nephew, James Oliver; and

Oliver’s wife, Mercy. Cicely does not rest in close proximity to her

enslavers, but rather near a burial mound used for Cambridge residents who succumbed

to smallpox.10 No stones with the

names of her grandparents, parents, brothers, or sisters encircle her memorial. Only

the headstone of another enslaved African woman, Jane, who was the servant of

Harvard steward Andrew Bordman and died nearly thirty years after Cicely, sits

nearby. Thus, racial identification fills the gaping hole where kinship should be,

for Cicely’s marker forever declares that she was a Negro, a girl of fifteen

whose short life was spent in perpetual servitude.11

This article foregrounds not her celebrated enslavers but Cicely herself,

reconstructing what can be gleaned of her and her world through an examination of

her gravestone in context, and acknowledging in that attempt the worth and full

humanity of her story. It also integrates the family history of the Brattles within

the broader development of slavery in New England. I position William Sr.’s

role in early ecclesiastical struggles and controversies at Harvard in the context

of increased slave importation and a local debate among his network of friends over

the ethics of slavery. I piece together Cicely’s story in the context of a

wider group of baptized enslaved women and elite puritan female enslavers to examine

how intimate realities and networks of female kinship and friendship were influenced

by enslavement. Cicely’s grave marker forms one link on a chain that connects

the slaveholding world and personal actions of William Brattle Jr. to the brutal

public execution of an enslaved woman named Phillis by burning at Gallows Lot (what

is now the corner of Massachusetts Avenue and Linnaean Street) less than a mile

north of Old Cambridge Burial Ground.12 Phillis’s trial offers a snapshot of the wider

enslaved community and uncovers the ways in which memory, social relationship, and

gender were central to the ways that commemoration was deployed against the

enslaved.

It is not just Cicely’s life but her labor that the Brattles

memorialized in stone. Service publicly ties her to “ye Reverend William

Brattle.” Cicely’s short English inscription contrasts William

Sr.’s long Latin memorial and would have been accessible to literate members

of the community, a population which, as Antonio Bly notes, included enslaved

people.13 Her tombstone was

meant to mark out not just the days of her life but to serve as an example for

others. She was part of the gendered labor of Black women and girls made legible by

Felicia Thomas that appeared in Boston’s early newspapers.14 That the memorialization of such labor also

appears in the material culture of early New England cemeteries highlights the

enslavers’ desire to make permanent sermons of racialized belonging and

alienation for later generations. The markers of Cicely’s family do not

surround her final resting place, but at the time of her birth a community of

enslaved people held by the Brattles and their friends had their names inscribed in

diaries, church ledgers, wills, and account books. They would have experienced the

physicality of Cicely’s life and passed the gravestone erected in her honor.

Scipio, one such person enslaved to William Sr., lived in the parsonage of

Harvard’s First Church as an unprofessed unbaptized person for at least seven

years. The house overlooked Harvard College and contained a garden and fields, a

cow, and fruit trees. Inside there were luxurious items and utilitarian pieces, as

well as an enormous library. He was not there primarily to pray or to study but to

work. Scipio’s name first appears in William Sr.’s diary on February

10, 1698.15 The Brattles also

employed a free white woman named Sarah Bradish as a domestic, whom they paid twelve

pounds a year, a figure that offers some sense of the value Cicely’s work

would have netted her had she been a free woman.16 During the spring of that year, William Sr.’s

diary contained descriptions of the construction of his garden, notations about

labor conspicuously marked by passive voice. On April 2, he recorded, “Goose

berry bushes planted and the first beans.”17 On April 4th, he wrote, “our garden was digged,

Bushes set and seed sown,” and on April 5th, he noted, “the great peas

and Boston peas were planted and also the carrots seed and parsnips sown. Oats

sown.”18 He wrote of

squashes and cucumbers planted, fields “plowed,” and a garden filled

with “red ears [of corn] and beans.” But the agent of

this work remains unacknowledged. It was likely Scipio who “planted,”

“digged,” “set,” and “sowed,” as by

December 7, William Sr. wrote that he had purchased “shoes for myself and

Scipio.”19

Scipio’s labor offered William Sr. the daily space to live the life of the

mind and mentor the next generation of Harvard men, but the minister’s wealth

was an inheritance created out of the Atlantic market of war, bondage, and merchant

capital. William Sr. was born into one of Boston’s wealthiest families on

November 22, 1662. The third child of the merchant Thomas Brattle and Elizabeth

Tyng, his family were signatory members of the Plymouth Patent. At the time of his

birth the Brattles and Tyngs owned considerable property in Boston, Maine, and Long

Island. His father Thomas Sr.’s fortune even underwrote King Philip’s

War.20 William Sr.’s

immediate family counted two older siblings, a brother named Thomas Jr. (b. 1658)

and a sister named Elizabeth (b. 1660); three younger sisters, Katherine (b. 1664),

Bethiah (b. 1666), and Mary (b. 1668); and a younger brother named Edward (b.

1670).21 They would grow up to

make alliances that would cement the elite status of their family for generations

and change the course of history. Their names and exploits would be used to shape

historical narratives of settlement, trade, and religion in the region and the

world. The Brattle houses, trading sites and merchant docks shaped the built

landscape of Boston and Cambridge—Brattle Square and Brattle

Streets—and physically inscribed their influence. Their stories were exalted

in the histories of the nineteenth century, and by the early twentieth century, the

work of the Harvard professor Perry Miller dominated the field of colonial American

history, and, coupled with that of his student, Yale’s Edmund S. Morgan,

created a widely accepted rubric within which to understand colonial New England and

the central tropes that contributed to the decline of puritanism.22

William Sr. was a founding member of this scholarly community. Along with his best

friend and former Harvard classmate John Leverett, William Sr. ran the school during

the absentee presidency of Increase Mather, writing a Latin primer on logic that

would be translated and used in the college for over a century.23 In his student Benjamin Colman’s

remembrance, Brattle was an “Able, Faithful and tender Tutor,” but he

also “search’d out Vice, and browbeat and punisht it with the

Authority and just Anger of a Master.”24 Though Benjamin was describing the relationship

between pupil and master, Jared Hardesty has noted that such hierarchies of power

underwrote the entire system of dependence.25 Scipio experienced William Sr.’s domineering

authority for two decades of enslavement, and the intellectual and spiritual

pursuits that filled William Sr.’s days and those of Colman and his coterie

of friends and colleagues were shaped by his intimate proximity. Scipio’s

labor, and those of other bonded people, afforded the Brattle brothers the time to

found the Brattle Street Church in Boston, a monument to his and his brother

Thomas’s rejection of the Mathers’ form of congregationalism.26 Both men sought to further

liberalize standards of baptism first introduced by the Halfway Covenant in the

1660s. Cicely’s baptism and those of other enslaved people were a part of

this process, but as Gloria Whiting argues, African-descended’ congregants used such

moments to publicly profess their own families and gendered connections.27 Both the Brattles and their

rivals, the Mathers, presided over the baptisms of considerable numbers of non-white

congregants, though there was some uneasiness about the relationship between baptism

and earthly freedom at the time.28 The stakes were not merely the conversion of unreached people but a desire to

augment numbers of congregants that subscribed to their perspective.

Scipio’s long unbaptized sojourn among the Brattles, and the timing of his

ultimate decision to enter into the covenant, highlights the role of work and

enslavement in William’s and Thomas’s place in the history of puritan

thought. The Brattle brothers’ religious philosophy embodied the shift in

puritan thinking that Sacvan Bercovitch has argued characterized the second

generation of American puritanism. During this period, individualism came into

conflict with communalism when many people did not enter into the church covenant

and therefore were not considered voting members in the colony. The decision to be

baptized was made by puritan parents, but the decision to become a “visible

saint” was a personal decision. That a large number of second-generation

puritans made decisions opposed to membership illustrates the larger conflict

between freedom and individualism in puritanism. Out of this conflict emerged the

Halfway Covenant which, “while retaining the premises of visible sainthood

… granted provisional church status to the still unregenerate children on the

ground that, in their case, baptism alone conferred certain inalienable covenant

rights.”29 The

communities that surrounded theologians such as the Brattles held increasing numbers

people in bondage, and such people caused some wary white enslavers to refuse to

baptize these individuals, worried such spiritual emancipation might become

physical.

Despite William Sr.’s theological influence and although other

African-descended’ people had been baptized by William Sr. at the First Church in

Cambridge in his first years of ministry, Scipio was not among them. In January

1688, William Sr. baptized “Philip [field], negro servant of

Mr. Danforth” in First Church, indicating the first known presence of Black

people in the First Church of Cambridge, which then lay within Harvard’s

gates and served as the college chapel.30 Their lives were pulled along lines of kinship and

friendship of the white congregants who filled the most prominent places in society,

but they were a central part of the social and political fabric of English

Protestant identity. A year before Cicely’s birth in 1697, William Sr.

married Elizabeth Hayman of Charlestown, a port with a bustling business to the West

Indies.31 Cicely’s grave

marker reflects the distinctive style of Charlestown’s Lamson family,

stonecutters whose workshop was situated near the dock, where indentured and

enslaved people worked.32 Elizabeth

grew up among neighbors who held slaves. An enslaved African man named Sambo toiled

for William Stitson, a deacon of First Church in Charlestown where her grandfather

had served as tithingman; when she was a child, another enslaved man escaped to

carry out a secret liaison with his chosen paramour, an enslaved woman who lived

nearby, flouting his owner’s wishes.33 As a child attending the First Church of Charlestown

with her family, she might have known the enslaved couple noted only as “Dan

Smiths Negro Mingo” and “Mr. Soley Negro” who were married at

the church in 1687.34

Regular interactions with enslaved people shaped the thinking of at least one member

of the Brattles’ wider network. On June 19, 1700, Samuel Sewall noted that he

comforted William Sr.’s sister Katherine as she stood at the burial of her

first husband John Eyre, who was laid alongside the graves of their nine children.

He wrote:

When I parted, I pray’d God to be favourably present with her, and

comfort her in the absence of so near and dear a Relation. Having been long

and much dissatisfied with the trade of fetching Negroes from Guinea; at

last I had a strong Inclination to Write something about it; but it wore

off.35

It is possible that the diary entry reflects the happenstance confluence of two

separate ideas occurring to Sewall at separate times on the same day, but it is also

possible that the funeral within a slaveholding family guided his thoughts towards

slavery. Scipio, two African women who toiled for Katherine’s sister

Elizabeth and Jeffrey, a Black mariner enslaved in Katherine’s sister

Mary’s household, were likely among the crowd that burial day.36 Additionally, the enslaved people

of Brattle’s elite friends may have made up a significant portion of those

gathered. The presence of enslaved Africans among the Brattles and those gathered

may have turned Sewall’s mind to “the trade of fetching Negroes from

Guinea.” The sight of so many of those enslaved Africans who had been

baptized by William Sr. himself standing among their mourning owners might have

prompted in Sewall this “strong Inclination to Write something about”

the slave trade.

Although Sewall indicated that the initial feeling of indignation “wore

off,” shortly thereafter he authored The Selling of Joseph, the result of both his increasing misgivings about the morality of the slave trade

and the perpetual servitude of enslaved Africans, many of whom had converted to

Christianity, and also his racist unease with the growing numbers of Black people in

the colonies. In it, he compared the holding of African slaves to the immorality of

the Biblical Joseph’s enslavement at the hands of his brothers. After writing The Selling of Joseph, Sewall distributed it to several close

friends, which most certainly would have included William Sr., his “Fast

Friend,” and ultimately entered a heated debate with John Saffin over the

matter of the promised freedom of Saffin’s slave, Adam.37

In The Selling of Joseph, Samuel Sewall described racial difference

as primarily affecting character, but his work also showcases Samuel’s

visceral disgust at the physical difference of people categorized as

“Negro”:

All things considered, it would conduce more to the Welfare of the Province,

to have White Servants for a Term of Years, than to have Slaves for Life.

Few can endure to hear of a Negro’s being made free; and indeed they

can seldom use their freedom well; yet their continual aspiring after their

forbidden Liberty, renders them Unwilling Servants. And there is such a

disparity in their Conditions, Colour & Hair, that they can never

embody with us, and grow up into orderly Families, to the Peopling of the

Land; but still remain in our Body Politick as a kind of extravasat

Blood.38

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines “embody” as “to

invest or clothe (a spirit) with a body” and includes John Healey’s

1610 translation of Augustine’s City of God describing

“Devills beeing imbodyed in ayre;” an image that the former Salem

witchcraft judge would have found familiar.39 William Brattle’s older brother Thomas Jr. had

penned a scathing rebuke of spectral evidence expressing a skepticism that was

strikingly modern and instrumental to turning public opinion against the

trials.40 But the ghost of such

spectral reasoning lingered as part of early modern scientists’ intellectual

worlds. If Africans were incorporated into the general spirit of Massachusetts

society, Samuel Sewall reasoned, the result would be a sick body. Indeed, the

African part, according to Samuel, would extravasate, or “force its way

out,” like contaminated blood leaking from an infected body. Samuel was

speaking a scientifically infused language that other like-minded lay doctors like

William Brattle and Cotton Mather would have understood. It was physical and

tactile, the language of examination. Invasive bodily inspections and harsh emetics

were prescribed to root out diseased “Conditions.” Indeed, in February

of 1700, the year before The Selling of Joseph was published,

William Sr. would self-prescribe “a vomit of ye wine physic” and

“hot ear & water porrage & feaver balsam (fennel) in warm water

for 30 hours.”41 His probate

inventory was filled with other such tinctures and remedies.42 Samuel turned a medical gaze towards the bodies

of African New Englanders, categorizing their Color as “disparity,”

his words evoking eyes and hands that inspected the hair of enslaved people like

Cicely, whose texture and care would have presented a stark difference. His remedy

for the body politic was the expulsion of Blackness and a regular infusion of

whiteness in the form of “White Servants for a Term of Years.”

The racial implications of the growing feud among the Mathers, Brattles, and Sewalls

spilled out when Cotton hotly defended his father’s threatened position as

president of Harvard College by directly referencing the slavery that had come to

shape how he too encountered the world. Believing Samuel to have supported the

Brattle opposition against his father Increase’s absentee presidency of

Harvard, Cotton stormed into the Boston bookseller Richard Wilkins’s

shop.43 He complained that

Samuel had “used his father worse than a Negar” and “spake so

loud that people in the street might hear him.” Cotton turned his attention

to Samuel’s son, folding the elder Sewall’s antislavery scruples into

his racially charged diatribe: “That one pleaded much for Negros” but

had “used” Increase “worse than a Neger.”44 In remembering the public shaming

of the moment, Samuel assigned the incidents to the margins, as if extravaset from

the main body of the text. Cotton made public sentiments that the jurist had taken

pains to circulate privately as the pamphlet The Selling of Joseph among a chosen coterie of friends.45 His intention was to dishonor Samuel, using a racially

infused slang that had been in circulation across the Northeast since the

seventeenth century.46 Sam did not

share his father’s misgivings about the trade and in later years locally

traded enslaved men and women.47

By the turn of the eighteenth century, Cambridge’s and Boston’s

lawmakers passed laws prohibiting any “Indian, negro or molatto servant, or

slave” from traveling abroad after nine o’clock because of the

“great disorders, insolencies and burglaries” which troubled

“her majesty’s good subjects.”48 Enslavers were required to post a bond of £50

before manumitting any “mollato or negro slave.”49 Nonetheless, on May 20, 1705, William Sr.

witnessed the will of his parishioner Peter Town, who painstakingly provided freedom

for Mingo, Charles, and Fidella, people enslaved by himself and his wife.50 He even provided an inheritance to

his “once negro servant Jane, who lives at Boston,” to have “ye

sum of five pound paid her within six months of my decease.”

Several weeks later, on June 10th, William Sr. baptized Mingo and Charles, alongside

Jeffrey “the negro servant of Mr. Goff,” and also Scipio, who had by

then been enslaved by Brattle for at least seven years.51 Scipio’s choice to be baptized alongside

two men destined for emancipation likely linked his profession with his desire for

freedom. It would be another fourteen years before Scipio would successfully

petition for his freedom, “praying the favour” of the Massachusetts

Court “that the estate of his said late Master may be Indemnified from any

Charge that may happen by him, in case he be made free.”52 The £50 charge would have made little

difference to the Brattles, but Scipio’s logic of fiscal responsibility was

the language he used to self-emancipate, as Brattle’s will left no written

provision for his freedom. The Brattles’ massive holdings sprawling across

two communities and several colonies formed the landscape of those people enslaved

by them. Bisected by the Charles River, it was a world shaped by the water as much

as the land.

Another man named Jeffrey was a sailor enslaved by William Sr.’s sister Mary

and brother-in-law John Mico. How he first gained experience on the water is

unclear, but sources indicate that by the summer of 1704, he had travelled the

Atlantic world. On May 6, 1703, John wrote a letter to Captain Samuel White

concerning Jeffrey on his voyage from Barbados to London, “I entreat you to

provide Care of him” and noted, “I have brought him up from a Child

and have avallue for him; but I commit him to You.”53 He also entreated the captain to allow Jeffrey

the liberty to visit the Mico family in London. Despite his concern for

Jeffrey’s welfare, any emotional “avallue” that John placed

upon the enslaved man was expressed in stark financial terms.54 By the time of his writing, John had been

married to William Sr.’s sister Mary for fourteen years and the two had no

living children. The Micos lived in a large house on School Street in Boston and

attended the Brattle Street Church.55 Such a lifestyle was owing to his merchant ventures

including a fish trade between New England and the Caribbean, which provisioned the

enslaved population on the islands with fish often in a condition too rotten to be

sold in New England.56 In eight

years, their household would also include a little girl named Cicely, who was owned

by William Sr. but lived frequently enough with the Micos to be presented for

baptism by Mary.

Despite their absence in the archival record, Cicely had parents and a natal

connection to Africa that condemned her to servitude and would be noted on her

gravestone in perpetuity. Perhaps one of the two African-descended’ women who toiled

for William’s sister Katherine Oliver and were enumerated as maids were known

more intimately as mother to Cicely. At the time of Nathaniel Oliver’s death

in 1704, he bequeathed the two women’s lives as part of a large estate with

property valued at ₤5250.7.10, including a “brick warehouse,

brew-house, salt-house, one fourth of windmill on Fort Hill, goods in warehouses to

the amount of ₤1260,” and his “house, stable, etc. in

Boston.”57 Whether or

not these women were related by kinship, they were linked by bondage. We can only

imaginatively reconstruct Cicely’s daily life from our fragments of knowledge

about the cultural and labor practices of other enslaved women in Colonial

Massachusetts. William Piersen noted the persistence of the African spinning

“on a stick centered on a plate, rather than with a loom,” as part of

the technique used by an African woman named Dinah enslaved in Salem.58 African histories were thus passed

down in the hands and labor of enslaved women, as they were in the sorrow songs,

pottery, and naming practices throughout the diaspora. Such weaving skills, Felicia

Thomas observes, were part of a young enslaved girl’s instruction and

highlighted in Boston’s slave-for-sale advertisements.59 Brattle’s probate inventory offers

possible clues into Cicely’s daily life: her work likely involved handling

the “brass kettle” and “pewter quart pot” listed

there.60 Servile work was

essential to Brattle, who hosted functions such as prayer meetings and meetings of

the Harvard Corporation, which convened in his home less than one month before

Cicely’s death. Formal gatherings would have meant presenting and handling

“China earthen, ware & glasses,” to elite attendees.61 A domestic like Cicely would have

mended Brattle’s expensive wardrobe using “Sowing & sticking

silk” and served countless cups of tea sweetened with “white

sugar” or perhaps drinking “chocolate,” products of slave

production that also appeared in the lines of the Brattles’ inventory.62 The “child’s whistle

with coral in it,” would have been diverting fun for the little boy who was

only three years Cicely’s junior but would have been looked after by workers

like Cicely. Boarded domestics would have slept on “old bedstead, cord and

strawbed” in the attic of the Parsonage as if stored alongside the “7

old pillows,” “4 old Trunks,” “an old chest & old

lumber.”63 Cicely’s intimate life can never be fully reconstructed from the scraps and

ephemera of her enslavers, but revisiting the context of such material evidence

emphasizes that for fifteen years she lived, and touched, and breathed, and was

known within a community of enslaved, bonded, and free people.

On February 7, 1714, Cicely stood before the community in Boston’s Brattle

Street Church at her baptism. At that event, she was identified not primarily as a

convert but as the negro servant to William Sr.’s sister Mary Mico.64 Although her epitaph memorializes

her as the servant of “ye Reverend William Brattle,” Cicely clearly

spent at least some part (if not most) of her life with Mary across the Charles

River in Boston. Mary was just as likely as her minister brother to have taken an

active role in Cicely’s conversion. As mistress of the house, Mary would have

shouldered the responsibility of religious education to household dependents, which

included the little girl whom they held in bondage. Cicely was noted as an adult in

the church register, in keeping with local tax laws that counted enslaved girls as

adults at fourteen, but also presented as a “dependent” of Mary,

starkly illuminating her liminal position in the community. Cicely may have been the

only little girl in the Mico household, as Mary and John had no children. On the

occasion of her baptism, Cicely needed to be conversant on two levels: communicating

her salvation experience in terms deemed satisfactory in a household with highly

specific religious expectations and remaining faithful to an interpretation of the

fifth commandment, which admonished lifelong obedience to her slave owners.65 Cicely’s life would have

been spent in service to an entire community of elite white women. William Sr.

painstakingly recorded their names and inheritances in his own will. He left money,

cows, medicines, and other things to nineteen women who were not relatives. He

entrusted Sarah Leverett, “sister loving, cousin carter & Elizabeth

hicks,” with carrying out the distribution of “several petty things

which shall be left when my family breaks up” including food, goods and

clothing “to my Christian neighbors & friends & poor

people.” Elizabeth and Ruth Hicks had cared for William Sr. after his ill

health caused by his battle with measles, four years earlier.66 In the event that his son did not outlive him,

he willed that his siblings be given two hundred pounds each and specifically that

his sister, Sarah Mico, who upon her own husband’s death in 1718 did not

inherit his house or goods, would be left “all my lands lying & being

in the Town of Cambridge.”67

Such women would have embodied many of the characteristics of the group Laurel Ulrich

famously termed “well-behaved women”:

Cotton Mather called them ‘the Hidden Ones.’ They never

preached or sat in a deacon’s bench. Nor did they vote or attend

Harvard. Neither, because they were virtuous women, did they question God or

the magistrates. They prayed secretly, read the Bible through at least once

a year, and went to hear the minister preach even when it snowed. Hoping for

an eternal crown, they never asked to be remembered on earth. And they

haven’t been. Well-behaved women seldom make history; against

Antinomians and witches, these pious matrons have had little chance at

all.68

But what did it mean to be a well-behaved Black woman in eighteenth-century Boston

and Cambridge? Cicely lived in a world dominated by the rhythms of sermons

and Bible Study. She lived in the shadow of academia but could not attend, and like

other such “well-behaved women” her life and history have been largely

forgotten by time. Tombstones erected by puritan enslavers and directed towards the

Black and white communities should be read as texts central to New England’s

religious culture.69 Black and

Native gathering for the deceased during times of death caused ruling Boston and

Cambridge residents to alter the auditory landscape of their communities. Instead of

tolling many times as it would for white funerals, for Black and Native people, the

bell would only toll once.70 The

silence that followed should be understood as a purposeful aspect of racialization,

even of the dead.

Cicely died on a Sunday in April, but she was not alone. The 1713–1714 measles

epidemic ravaged the young population of Brattle Street Church, occasioning Benjamin

Colman to preach and ultimately publish a sermon entitled A Devout

Contemplation On the Early DEATH Of Pious and Lovely Children.71 The Sermon was given in

remembrance of “Mrs. Elizabeth Wainwright. Who departed this life, April the

8th. 1714.” Elizabeth was one year younger than Cicely and was also a

baptized member of Brattle Street Church. Rev. Colman addressed his sermon to the

youth of his flock and also named the “son of Major Fitch” as having

also died. And while he did not explicitly name Cicely, vestiges of her story can be

read in the lines of Colman’s text to his surviving flock, which would have

included Mary Mico, who had recently buried Cicely. He opined, “Again, The

Death of pious Children teaches us this also of a Principle of Grace, that where it

once is, the Soul is safe. Let Death come as soon as it will after a persons

Coversion [sic], when once a Sanctifying Change has

passed on him, be he never so young, the Soul is safe.” Cicely’s

baptism in February was quickly followed by her death in April, a pattern that

Colman called out for special mention. He ended his sermon with an allusion to the

Joseph story when he urged, “We must not repeat Jacobs Error, who supposed himself bereaved, when Joseph was only Advancing under the special Favour of Providence in Another Countrey.” Joseph had not indeed passed over the

veil of death but had been sold by his brothers to slavery in Egypt, a specificity

that Colman would have readily known as he would have also known the furor caused by

Sewall and Saffin’s public row over the antislavery interpretation of the

Joseph story in light of the enslaved African-descended population.

Cicely’s life in colonial Cambridge was filled not only with religious rites

but also death and racial violence. On February 15, 1712, Samuel Sewall recorded

that William Sr. “prayed at the place of Execution,” for an enslaved

man named Mingo who had been sentenced to death “for forcible

Buggery,” against Abigail Dowes, and another unidentified person. Mingo was

enslaved to Wait Winthrop, who was married to Katherine, William Sr.’s

sister, and lived near the Micos.72 The trial record offers the bawdy “Cocke” as an alias for Mingo, an

appellation that historian Jim Downs notes as an example of the hypersexualized

stereotype placed upon Black men and the scholarly origin story that roots

homosexuality in the colonial world with Black criminality.73 Cicely’s enslavement intersected Mingo,

and it is not unreasonable to assume that she would have had knowledge of the

uproar. She would have heard the casual appellation meant to evoke shame and may

have had to call him by the denigrating name. She might have also known Abigail, who

was the same age as she and lived in the community. Two months later news poured

into Boston of a New York slave revolt, with the News-Letter detailing,

“‘tis fear’d that most of the Negro’s here (who are very

numerous) knew of the Late Conspiracy to Murder the Christians; six of them have

been their own Executioners by Shooting and cutting their own Throats”74 Benjamin Colman himself wrote the

following to his friend Robert Woodrow:

We are serv’d here in this Town very much by blacks or Negro’s

in our Houses. Scarce a House but has one, excepting the very poor. Those

slaves grow disorderly, taking their time in the nights for diverse

wickednesses. The Town at one of their Meetings took this into

Consideration, and ordered that no Negro should be in the Street after nine

in the Evening without a ticket from his master; and if any were so found

they should be had to the House of Correction and whippt 6. or 7. lashes.

When a few of ‘em had been served so, fires were kindled about Town

every day or night; the cry of fire terrified us from time to time; one fire

only prevailed (thro’ the mercy of God) and burnt down two smal

Tenements: twenty others were discovered in their kindling. At last one or

two Negroes appear’d Guilty, and one was prov’d so and is

condemned to die. And so we sleep in peace again thro’ the favour of

God to us.75

For Benjamin, the “just anger” of a slaveholding community called for

“the House of Correction,” the punishment of being “whippt 6.

or 7. Lashes,” or even death. His was an elite world surrounded by the

enslaved, one filled with disorder, wickedness and dark designs. It was one enforced

by the lash and secured by public execution. And it was in this world that Cicely

lived and died.

By the time that Colman slept “in peace again thro’ the favour of

God,” after the policing and execution of Black people, Cicely had been dead

for a decade. Similarly deceased were Elizabeth and William Brattle, as well as

hundreds of others, felled by the measles epidemic that tore through New England and

its lingering syndromes. The week that Cicely died, the News Letter ran an advertisement for a pamphlet by Cotton Mather, entitled “A Perfect

Recovery, Being what was Exhibited at Boston–Lecture to the Inhabitants after

they had passed thro’ a very Sickly Winter. With some Remarks on the shining

Patterns of Piety, left by some very Young Persons, who Dyed in the common

calamity.”76 Mather had

lost his own wife, Maria; infant twins; and three-year-old daughter in the

“Sickly Winter.” Nearly thirty years later, a tombstone would be

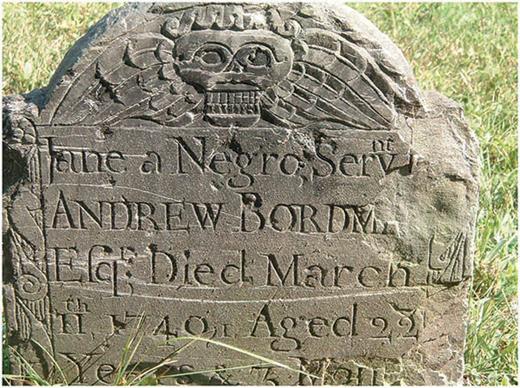

erected to a Black woman, lost during another deadly epidemic.77 The epitaph reads:

Jane a Negro servnt [damaged]

Andrew Bordman

Esqr; Died March

11th, 1740 Aged 22 Years & 3 months.

Fig. 2.—

Grave marker for an enslaved girl named Jane. Photo provided by the author.

The Bordman family papers list the names, relationships, and birth dates of

Jane’s family, including her mother, Rose, who would have been

Cicely’s contemporary and whose name preceded the names and birthdates of

four children—Jane, Flora, Jeffrey, and Cesar—born between 1718 and

1733.78 Rose was a member of

the Christian community in Cambridge and was baptized in February 1730.79 In 1741, Andrew Bordman Jr. noted

Jane’s death in his journal, writing:

Jane—(after Recovering of a Throat distemper to such a measure of

health as to get down Stairs and abroad) was taken ill of a Languishing Slow

Feavour of which She Lay ill 24 days and then Expired 11 Mar 1740/1

about half an hour after Nine oClock P.M. Aged 22 years 3 months and 6 days.

Buryd 13day.80

Jane, like Cicely, died during an outbreak, and the evidence of the almanac makes the

case ironclad that she perished from diphtheria, scarlett fever, or, as it was known

in the early eighteenth century, “throat distemper.” Jane, like

Cicely, was given a marked burial in Old Cambridge Burial Ground. In the space

between their two gravestones lies a community history of disease, death, and

domestic insurrection. Between Cicely and Jane’s deaths in 1714 and 1741,

respectively, a smallpox crisis gripped Boston, inflaming racial tensions. Mather,

an amateur scientist and a member of the Royal Society, turned to his slave Onesimus

and the enslaved community for a defense against the ravages of smallpox in 1721.

Several years earlier, Onesimus reported to Mather that he had “undergone an

Operation, which had given him something of the Small-Pox & would forever

praeserve him from it; adding that it was often used among the Guramantese.”

When smallpox swept through the colony during the summer of 1721, Mather and William

Brattle’s former student and eulogizer Benjamin Colman interviewed enslaved

people in Boston about their experiences of smallpox inoculation in Africa. Mather

and Zabdiel Boylston submitted Boylston’s son as well as his enslaved man

servant and child as test subjects. The consultation of Black people caused a

strident debate in Boston, but the inoculation bore favorable results.81 On its heels, a five-year long

diphtheria epidemic ravaged New England, beginning in the town of Kingston, New

Hampshire in 1735 before spreading up through Maine and down through Massachusetts

and Connecticut, ultimately killing 5,000, including Jane. At the same time,

smallpox was ravaging South Carolina, killing up to a quarter of white colonists who

caught the disease, but only half as many Black people (as many had prior exposure).

In late 1739, a group of enslaved people used the opportunity presented by this

epidemic and their Angola religious cosmologies to overthrow their enslavers and try

to escape in what would come to be called the Stono Rebellion.82 Just seven days after Jane’s death and

six months after the Stono Rebellion, the first in a series of fires broke out in

New York. With the memory of Stono still fresh, these events would ultimately spark

fears of a wide-ranging slave conspiracy, planned with the help of local poor

whites, which would lead to the public execution of thirty people as well as the

mass deportation of seventy others. Less than one mile north from Cicely and

Jane’s final resting place is the execution grounds of Cambridge Common, the

location where another enslaved woman named Phillis was burned at the stake in

1754.

Cambridge and Boston’s enslaved community in midcentury had become augmented

by the arrival of Caribbean transplants. Such white and Black Barbadian emigrees

moved in alongside the Brattles in a neighborhood of mansions that ran towards

Harvard College and would come to be known as Tory Row.83 But bonded people were connected in larger

communities that stretched from Cambridge to Concord, Boston to Charlestown. The

broader world of two enslaved people—Phillis, enslaved as a child to John

Codman in Charlestown, and Robin, to the Vassalls—intersected Jane and her

family, as well as Philicia, Zilliah, and Rose.84 The familiar geographies of local life would have

included the burial ground that faced Harvard College, which already contained the

decorative memorial to Cicely’s life and death, as well as the execution area

of Boston Common, where another woman named Maria was burned to death three decades

earlier, executed alongside two enslaved Black men who were hanged.85 The social world of William Jr.,

the little boy left behind when William, Elizabeth, and Cicely died, was likewise

marked by landmarks of enslavement. He was orphaned at the age of eleven but

inherited one of the largest fortunes in the colony and attended Harvard College. In

1728, during his time at the college, Cambridge passed laws against street gambling

attributed to “young people, servants & negroes.”86 He maintained connections to his

parents’ circle of friends, people like Andrew Bordman and Elizur Holyoke. He

also deepened his social ties in New England’s regional elite by marrying

Katherine Saltonstall, daughter of Connecticut Judge Gurdon Saltonstall. Andrew

listed the births of William Jr.’s children, Thomas and Elizabeth, in his

almanac.87

The stories told by the memorials to enslaved female “servants” in the

municipal burial ground were meant to resonate with the next generation. Such

markers emphasized lifelong service to recognizable elite families and conversion to

the Christian faith. Family connections were erased, though it is likely that the

enslaved community carried some knowledge of the connection that Cicely, and later

Jane, had to their own communities. They would have inhabited the same spaces as

their ancestors, cramped attics, and tended the same gardens. But some might also

have been housed in slave quarters, as was the case of those enslaved by the Royals.

This change in the physical geography of the era termed the “Refinement of

America” is one that has been primarily told from the point of view of white

consumers and not of the Black and brown people whose lives were consumed.88 At the same time, William

Jr.’s fortunes rose during this era of opulence, and he bought a mansion

located on Brattle Street, with gardens and a mall that led to the Charles River.

His neighbor, Henry Vassall, was one of the largest slaveholders in the region, and

the two men housed enslaved people in their attics.89 William Jr. filled his home with treasures and

supplied his daughter with a lavish dowry which he placed in an iron chest.90 In April 1752, smallpox ravaged

Cambridge and, attempting to escape the outbreak, the Brattles left their mansion in

Cambridge for the countryside. They left their enslaved man Dick behind to face the

disease.91 Neighbor Henry

Vassall had likewise quit the area for the socially distanced safety his resources

could offer, creating an opportunity for his enslaved man Robin to effect his

escape. Working in concert with a white indentured servant, Robin and Dick made off

with William Jr.’s iron chest. It contained a fortune, more than enough to

finance Robin’s planned escape, first to New France and then to France. But

the splendor of his haul made it impossible to fence, and the two men were caught

and imprisoned in Concord.92

William Jr.’s attempt to flee the disease in the countryside had been

unsuccessful. His wife died of smallpox just a week after they quit the college

town. His return to Cambridge and Robin’s subsequent trial set a series of

events in motion that upended the enslaved community.93 Following the trial, William Jr. was awarded more than

just his daughter’s dowry: he was given Robin’s life to

“dispose of” as he wished.94 He sold him to his colleague Dr. William Clark, an

apothecary who lived in Boston. Three years of enslavement to Clark had furnished

Robin with a knowledge of poisons. When his friend, Mark, approached him complaining

of his recalcitrant master named John Codman, who was keeping him from visiting his

wife and child in Boston, as well as physically and sexually abusing his

bondspeople, Robin offered a deadly solution.95

But the poisoning’s domestic setting and its relationship to Black and white

women’s intimate lives, presented in stark gendered and religious terms, is

preserved in the court record. A, by then, elderly Phillis administered the poison,

after Mark had “read the Bible through” and determined that they could

guiltlessly kill John by refraining from “bloodshed.” After what must

have sounded to the elite white court as a familiar yet disordered Bible study, the

male action in the case dropped away, save for John who was acted upon. On

“the Sabbath day morning before the last Sacrament,” it was

“Phebe and Phillis” who “made a solution which they kept

secreted in a vial” and “mixed with the water-gruel and

sago.”96 Such testimony

must have been uncomfortably close to William Jr.’s own memories of his

father’s last moments being tended to by female domestics using physics and

cures. Indeed, the poison was sometimes given by the enslaved women, but also,

unknowingly, by John’s daughters.97 The dependence of the white household women on the

knowledge of enslaved women, one that ultimately led to them unknowingly committing

patricide, was a stark inversion of the funeral sermons memorializing white women

nursing ailing servants. Benjamin Colman (William Sr.’s former student) had

eulogized his daughter, Mary Colman Turell, in 1735, writing: “To her Servants she was good and kind, and took care of them,

especially of the Soul of a Slave who dy’d (in the House)

about a Month before her.”98 Indeed, according to Phillis, his daughter Molly had discovered the lead that they

had used to poison his porridge, and asked Phillis “[w]hat it

was.” When she “told her I did not know,” Mary did not press

the issue.99 Similarly, her sister

Betty noticed that the “watergruel” had “turned yellow,”

and she asked Phillis about it. Phillis “gave her no answer” but

instead threw it away and was not questioned.100

On August 29, 1755, William Jr. was subpoenaed to give witness against Mark and

Phillis, which he did on the following day. He faced a court presided over by

Stephen Sewall, Samuel Sewall’s son.101 The judgement given by the court was brutal. Mark was

ordered to be publicly hanged and after death his body gibbetted, while Phillis was

ordered to be burned at the stake. Phillis would not have been a stranger to William

Jr., as she testified that she was purchased by John Codman “when I was a

little girl” in Charlestown, where William Jr.’s mother’s

family lived.102 That Phillis was

part of the interconnected community of enslavers and enslaved people that

surrounded William Jr. is evident when she said that she knew Robin, who had grown

up next door to William and shuttled between Cambridge and Charlestown, “for

many years.”103 Mark and

Phillis’s execution was attended by a massive crowd. The Boston

Evening Post featured the execution:

The Fellow was hanged, and the Woman burned at the Stake about Ten Yards

distant from the Gallows. They both confessed themselves guilty of the Crime

for which they suffered, acknowledged the Justice of their Sentence, and

died very penitent. After Execution, the Body of Mark was

brought down to Charlestown Common, and hanged in Chains,

on a Gibbet erected there for that Purpose.”104

Was William Jr. among the massive crowd that attended the execution? If he

heard Phillis’s final “penance” followed by shrieks of agony,

did he remember the little enslaved girl named Cicely whom he had known as a boy,

who was buried just a short walk away? William Jr.’s friend John

Winthrop noted the brutality of the execution in the margins of his almanac,

writing, “a terrible spectacle in Cambridge 2 negro’s belonging to

Capt. Codman of Charleston executed for petit treason, for murdering their said

master by poison. They were drawn upon a sled to the place of execution; &

Mark, a fellow about 30, was hanged; & Phillis, an old creature, was burnt to death.”105 John’s shock at the spectacle is encapsulated

in his underlining of “burnt to death” and his use of the descriptors

“an old creature” to describe Phillis. Indeed, it was only the second

time that an enslaved person (both times a woman) was executed publicly in such a

way in Massachusetts, and at the first instance, Cotton Mather had described the

execution of Maria as “a picture of hell, too, in a negro then burnt to death

at the stake.”106 But the

public execution of an elder within the enslaved community must have been a seismic

shock to the people enslaved within close proximity to the burning. In contrast to

white antinomians and witches, infamy did not offer Phillis and other non-white

women a place in history. Her punishment was meant to consume—her life, her

body, and her memory. After execution, Mark’s body was placed in a gibbet

along the road to Charlestown as a physical public warning to the community both

enslaved and free, a gruesome memento mori. Years later in Paul Revere’s 1798

letter to Jeremy Belknap, he used Mark’s remains as a geographical landmark

to indicate the location where he came upon British regular troops in 1775:

“After I had passed Charlestown Neck, and got nearly opposite where Mark was

hung in chains, I saw two men on Horseback, under a Tree. When I got near them, I

discovered they were British officers.”107 Though Mark’s remains no longer hang in

Charlestown, Cicely and Jane’s gravestones endure as physical markers to the

interconnected lives and deaths of those enslaved by Cambridge’s elite.

On February 23, 1760, Cato Hanker, a free Black man from Cambridge who served in the

Massachusetts colonial militia, requested his pension for fighting in the Seven

Years’ War. He chose then Captain William Brattle Jr. to pen his petition:

“Cato Hanker, a free negro in Cambridge humbly sheweth that March last he

enlisted himself a souldier in the Provincial Service against Canada by your

Excellency’s order went to Castle William from thence went to Crown Point

where he remained until orderly dismissed.”108 William Jr.’s family owned the land at Crown

Point where he had been stationed to command and likely knew Cato from within his

own Cambridge community. In petitioning for his pension, Cato Hanker was

participating in a form of public protest that members of the enslaved community

would use in order to petition Massachusetts’s courts for freedom.

William Jr. too was also increasingly engaged in public protest. In 1765, incensed by

the duties levied by the British government, he became a member of the Stamp Act

Congress. But by 1771, his fortunes, and political sensibilities had shifted when he

was made major general of the royal militia.109 That same year, Ebenezer Pemberton, grandson to

William Sr.’s friend and ministerial colleague, published a sermon in memory

of George Whitfield. At the end, he included a poem penned by an enslaved girl with

a genius for writing named Phillis Wheatley.110 William Jr. would have likely known this Phillis who

was feted in the homes of Boston and Cambridge elites, as he had the other Phillis

whose public burning had been the result, in part, of his testimony. In 1771,

Phillis Wheatley was baptized at Old South Church into the congregation of the

Brattle Street Church that had been founded in 1699 by William Jr.’s father

and his uncle Thomas, the same congregation where Cicely had also been

baptized.111

Circumstances for the enslaved and free community were changing rapidly. In 1772,

James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw’s narrative describing the horrors of the

slave trade was published, and the Somerset case directly challenged enslavement in

Britain, a precedent Boston’s slaves read as an opportunity. In 1773, while

William Jr. supported Governor Gage’s notion that the judiciary be rightly

limited by the crown, engaged in a public debate with John Adams, was selected to

represent Massachusetts in a committee, and was tasked with drawing the divide with

New York, Benjamin Rush offered his own appeal against the slave trade, including

Phillis as an exemplar of the talents of the enslaved.112 The same year, Peter Bestes and other free and

enslaved people petitioned the Massachusetts Courts for freedom.113 By 1774, a private letter sent by William Jr.

warning General Thomas Gage of military supplies sent from Boston was intercepted

and published in an incident known as the Powder Alarm. Following the incident,

Brattle left Cambridge forever, retreating initially to Boston.

Unlike Cicely, William Jr. is not buried in Old Cambridge Burial Ground. The last

published mention of William Jr. in his birth country appeared in the Boston

Evening Gazette a year before his death, detailing his

“flight” from “Boston to Halifax,” and derisively

arguing that the rich scion had only “a singular talent at running

away.”114 Forced to

evacuate Boston in 1776, William Jr. left with Black loyalists like printer Boston

King. His unmarked remains lie in Halifax, far from the rest of his family.115 But while William Jr.’s

bones are not interred in Cambridge, his name graces sites across the Northeast,

from Brattle Street in Cambridge to Brattlesboro, Vermont.116

On January 13, 1798, the Providence Gazette ran a notice of the

death of “Dinah, a black woman, at the house of Thomas Brattle, Esq.

Cambridge, Mass, aged 100 years.”117 In her century of life, she might have known Cicely,

Scipio, Jane, and so many others. Indeed, she was born in 1698, a year before

Cicely, and, at her death, she was enslaved to Thomas, William Jr.’s son. On

May 6, 1782, Thomas’s daughter, Katherine Brattle Wendell, who had remained

on the Brattle property during the Revolutionary War while her father and brother

fled, petitioned to remain in the estate. She wrote of her privation at being forced

to maintain the expenses of the house alone while being compelled to host Patriot

leaders such as George Washington and added, “Besides your memorialist has

been at the expense of maintaining an aged slave left of the aforesaid estate, who

has for year been incapable of service, and who must be considered as an incumbrance

on the estate.”118 That

“aged slave” was most likely Dinah, who was eighty-four at the time of

the petition and would have been attached to the family estate in Cambridge that was

ultimately claimed by Thomas. She would have, like Cicely before her, been passed

between siblings in the Brattle family, forced to toil and to follow the

circumstances of their lives. By the time that the notice of Dinah’s death

ran in the Providence Gazette, so much had changed from when

Cicely’s own memorial was etched in slate. The colonial world had given way

to a new republic, and by 1782, enslavement had officially ended in Massachusetts,

although racial segregation, inequity, poverty, and violence endured. But some

geographies of that enslaved past, such as Cicely and Jane’s tombstones,

remained for three more centuries, as weathered tombstone memorials etched in

curlicue writing and antiquated symbology. Despite their location among divines and

elites whose histories have inspired of early America, precious little has

been written of them in nearly three centuries. In contrast, our oldest libraries

are filled with evidence and ephemera of the lives of their captors: papers and

diaries, account books and wills. Black, female, and enslaved, Cicely and Jane were

not meant to be remembered, and for three hundred years, they largely have not been.

In a world where well-behaved white women seldom make history, Cicely and

Jane’s stories, seem to have been even more fated to fade into the silence of

the past. But, perhaps, such expectations betray the assumptions of later ages.

Etched in stone, they were intended to endure, and offer memorial to the social

meanings of race, labor and memory. In the space between Cicely and Jane’s

tombstones lie the possibilities to interpret the meaning of their lives anew.

1Considerable work is being done on excavating Black graveyards and graveyards

with markers to African and African-descended’ people in New England. As far as

I am currently aware, the oldest extant markers for enslaved people exist in

Rhode Island’s “God’s Little Acre,” but those were

erected a few years after Cicely’s memorial. Of course, the act of

marking is culturally situated, with many West and Southwest Africans choosing

very different methods to honor the memory of deceased people. Slate markers

themselves are an English tradition, contrasting the sandstone used in early

Dutch colonies which have not survived; thus, the survival of

Cicely’s’ marker must be analyzed sensitively, taking into account

different cultural modes of commemoration. For current work on African and

African American graveyards, see Glenn A. Knoblock, African American

Historical Burial Grounds and Gravesites of New England (Jefferson,

NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2015). Caitlin Galante

DeAngelis Hopkins has done considerable work analyzing New England’s

graveyards historically. Of particular note to this article, she briefly

mentions Cicely and Jane’s markers in a rigorous and highly useful

discussion of New England’s slave burials. Caitlin Galante DeAngelis

Hopkins, “The Shadow of Change: Politics and Memory in New

England’s Historic Burying Grounds, 1630–1776” (PhD diss.,

Harvard University, 2014), 110–11. For work that contrasts the material

survivability of markers across cultures, see Brandon Richards, “Hier

Leydt Begraven: A Primer on Dutch Colonial Gravestones,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 43, no. 2 (2014):

1–22.

2Samuel Sewall, The Diary of Samuel Sewall, ed. M. Halsey Thomas

(New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1973), 2:752.

3Although it remains convention to refer to historical actors by their last name

after the first full instance of their name, I consciously break with this

practice. Enslaved people were most frequently not given a family name and only

identified by “Negro,” “Mulatto” or some other

physical characteristic. I have opted to refer to everyone by their first name

where clarity permits.

4In contrast to the placement of Cambridge’s enslavers within long

historiographies of New England history, no similarly extended engagement exists

for Cicely or Jane. Recent sermons and ongoing essay projects spearheaded by the

First Church of Cambridge to reckon with the congregation’s slaveholding

past highlighted the gravestone’s uniqueness and sought to foreground the

lives of such enslaved African people owned by early ministers and congregants.

First Church of Cambridge, “Owning our History,” 2018, https://www.firstchurchcambridge.org/owning-our-history/;

“Enslaved Africans and Native Americans at First Church in

Cambridge,” https://www.firstchurchcambridge.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/TriptychFinal_10.4.19-1.pdf;

“Owning Our History: First Church and Race 1636–1873,” https://www.firstchurchcambridge.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Owning-Our-History.-First-Church-and-Race.pdf;

and James Ramsey, “Stories Impossible to Tell: Meditations on the History

of Slaveholding at First Church in Cambridge,” accessed October 1, 2021, https://www.firstchurchcambridge.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Stories-Impossible-to-Tell-Full.pdf. There has

been no extended historical analysis of her grave marker aside from the mention

that I made of Cicely’s story in my 2013 dissertation, but recent work

directed towards a broader audience has begun the process of highlighting the

importance of such narratives: Nicole Maskiell, “Bound by Bondage:

Slavery Among Elites in Colonial Massachusetts and New York” (PhD diss.,

Cornell University, 2013), 71–88; Maskiell, “Cicely was young,

Black and enslaved – her death during an epidemic in 1714 has lessons

that resonate in today’s pandemic,” The

Conversation, December 2020, https://theconversation.com/cicely-was-young-black-and-enslaved-her-death-during-an-epidemic-in-1714-has-lessons-that-resonate-in-todays-pandemic-147733 (accessed February 24, 2022); Stephen Smith and Kate Ellis, “Shackled

Legacy: Universities and the Slave Trade,” Podcast, September 4, 2017, https://www.apmreports.org/episode/2017/09/04/shackled-legacy;

Hopkins, “The Beautiful, Forgotten and Moving Graves of New

England’s Slaves,” October 26, 2016, Atlas

Obscura,https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-beautiful-and-forgotten-gravesites-of-new-englands-slaves;

C. Ramsey Fahs and Emma K. Talkoff, “Harvard Yard, Uncovered,” Harvard Crimson, November 19, 2015, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2015/11/19/harvard-yard-scrut-2015/;

Jeff Neal “Amid the Old Burying Ground,” The Harvard

Gazette, October 28, 2015, https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2015/10/in-the-old-burying-ground/;

and Sven Beckert, Katherine Steven, and the students of the Harvard and Slavery

Research Seminar, Harvard and Slavery: Seeking a Forgotten

History,https://www.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/content/Harvard-Slavery-Book-111110.pdf.

5Annette Gordon-Reed’s recentering of the narrative of Thomas

Jefferson’s enslaved family members ushered in a seismic shift in

widespread engagement with such non-white histories, although it also spawned a

similar degree of scholarly backlash devoted to deploying the archival records

to call into question such narratives. Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham centered the

need “to bring race more prominently” into “analyses of

power.” Thavolia Glymph and Stephanie Jones-Rogers have centered a female

world within slaveholding households in the early South, an essential framework

to engage in an extended gendered and racial analysis of slavery and imagine

white female enslavers as active agents of enslavement. Jennifer Morgan’s

work offered an indispensable framework with which to engage with gender, labor,

and the physicality of enslaved women’s bodily production as crucial to

the emergence of racial notions of black inferiority and white supremacy.

Annette Gordon-Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American

Family (2008; repr., New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009);

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, “African-American Women’s History and

the Metalanguage of Race.” Signs 17 (1992): 252;

Thavolia Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the

Plantation Household (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press,

2008); Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property: White Women as

Slave Owners in the American South (New Haven: Yale University

Press, 2019); Jennifer L. Morgan, “‘Some Could Suckle over Their

Shoulder’: Male Travelers, Female Bodies, and the Gendering of Racial

Ideology, 1500–1700,” William and Mary Quarterly 54 (1997): 167–92; and Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and

Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

6Wendy Warren, New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early

America (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2016); Gloria

McCahon Whiting, “Power, Patriarchy, and Provision: African American

Families Negotiate Gender and Slavery,” Journal of American

History 103 (2016): 583–605; Whiting, “Race, Slavery,

and the Problem of Numbers in Early New England: A View from Probate

Court,” WMQ 77 (2020): 405–40; and Jared Ross

Hardesty, Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century

Boston (New York: New York University Press, 2016).

7For more on the archive as a site of power, see Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the

Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017);

Carolyn Steedman, Dust: The Archive and Cultural History (New

Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2002); Natalie Zemon Davis, Women on the Margins: Three Seventeenth-Century Lives (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997); and Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1995; repr., Boston: Beacon Press, 2015). For an excellent overview of the ways

in which the continental Dutch historical narrative, which largely erases

slavery, was shaped by a conscious manipulation of the archive, see Dienke

Hondius, Blackness in Western Europe: Racial Patterns of Paternalism and

Exclusion (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2014), 2; and

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe

26 12, no. 2 (2008): 2, 12.

8Bernard Bailyn, The New England Merchants in the Seventeenth

Century (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1955); Sacvan

Bercovitch, The American Jeremiad (Madison: University of

Wisconsin Press, 1978); Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, “Vertuous Women Found:

New England Ministerial Literature, 1668–1735,” American

Quarterly 38 (1976): 20, 35; and Mary Beth Norton, Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American

Women, 1750–1800 (1980; repr., Ithaca: Cornell University

Press, 1996).

9Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the ‘Spirit’ of

Capitalism and Other Writing, ed. and trans. Peter Baehr and Gordon

C. Wells (1905; repr. New York: Penguin Books, 2002), 14.

10A Self-Guided Tour of The Old Burying Ground, Collections of the

Cambridge Historical Commission, 2.

11For a wonderful reading of Elizabeth Freeman’s grave, situated among the

Sedgwick family of Sheffield, see Sari Edelstein, “‘Good Mother,

Farewell’: Elizabeth Freeman’s Silence and the Stories of

Mumbet,” New England Quarterly 94 (2019):

584–614.

13Antonio T. Bly, “‘Pretends he can read’: Runaways and

Literacy in Colonial America,” Early American Studies 6

(2008): 261–94.

14Felicia Y. Thomas, “‘Fit for Town or Country’: Black Women

and Work in Colonial Massachusetts,” Journal of African American

History (2020): 191–212.

15Brattle’s diary entries are reprinted in William Newell, The

Pastor’s Remembrances: A Discourse Delivered Before the First Parish

in Cambridge on Sunday, May 27, 1855 (Cambridge, MA: John Bartlett,

1855), 34. The Bradish family lived in Cambridge and Boston and were neighbors

of the Brattles. Lucius R. Paige, History of Cambridge, Massachusetts,

1630–1877, with a genealogical Record, accessed October 21,

2020, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0228%3Achapter%3D27&force=y.

16Newell, The Pastor’s Remembrances, 34.

17Newell, The Pastor’s Remembrances, 139–41, 152,

174.

18Excerpts from William Brattle’s Diary in Records

of the Church of Christ at Cambridge in New England, 1632–1830,

comprising the ministerial records of baptisms, marriages, deaths, admission

to covenant and communion, dismissals and church proceedings (Boston: E. Putnam, 1906), 290–93.

19Newell, The Pastor’s Remembrances, 34.

20Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougias, King Philip’s War: The

History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict (1999;

repr., New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2017), 73.

21Rick Kennedy, “William Brattle in A Compendium of

Logick,” in Aristotelian and Cartesian Logic at

Harvard, ed. Rick Kennedy (Boston: The Colonial Society of

Massachusetts, 1995), 67:110.

22Perry Miller, The New England Mind, From Colony to Province (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1953); and Edmund Morgan, Visible Saints: The History of a Puritan Idea (1963; repr.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985).

23Brattle’s other published works were An Ephemeris of Celestial

Motions … , published in 1682, and Almanack of the

Coelestiall Motions, published in 1693. Harvard College used

Brattle’s Compendium Logicae Secundum principia as a

textbook until 1765. John Langdon Sibley, “William Brattle,” in Biographical Sketches of Graduate of Harvard University, in

Cambridge, Massachusetts,1678–1689 (Cambridge, MA: Charles William Sever,

University Bookstore, 1885), 3:206–7. For more on Brattle and Leverett’s

administration of Harvard College during the absentee presidency of Increase

Mather, see Rick Alan Kennedy, “Thy Patriarch’s Desire: Thomas and

William Brattle in Puritan Massachusetts” (PhD. diss., University of

California, Santa Barbara, 1987), 3–6.

24Benjamin Colman, A Sermon at the Lecture in Boston, After the Funerals of

Those Excellent & Learned Divines and Eminent Fellows of Harvard

College The Reverend, Mr. William Brattle … (Boston: Printed

by B. Green, for Samuel Gerrish and Daniel Henchman, 1717), 32.

25Hardesty, Unfreedom, 2.

26Mark Valeri argues that religion and commerce were intertwined in New England and

that the visible establishment of churches by such merchant elites was central

to the process. Valeri, Heavenly Merchandize: How Religion Shaped

Commerce in Puritan America (Princeton: Princeton University Press,

2010), 20; and Kennedy, “Thy Patriarch’s Desire,”

5–6.

27Whiting, “Power, Patriarchy, and Provision,” 598.

28Cotton Mather’s 1706 slave catechism, included in his pamphlet The

Negro Christianized, was intended to induce slave masters to

baptize their slaves without the worry that Christianization caused

emancipation. Such an emphasis highlights that baptism’s association with

earthly freedom remained concerning enough in the opening decade of the

eighteenth century to cause many slaveholders to refrain from baptizing their

slaves. Cotton Mather, The Negro Christianized: An Essay to Excite and

Assist that Good Work, the Instruction of Negro-Servants in

Christianity, ed. Paul Royster (1706; repr., Lincoln: Libraries at

University of Nebraska-Lincoln Electronic Texts in American Studies, 2007),

24–26.

29Bercovitch, American Jeremiad, 63.

30Stephen Paschall Sharples, comp. and ed., Records of the Church of Christ

at Cambridge in New England, 1682–1830 (Boston: Eben Putnam,

1906), 59 (hereafter cited as Rec. First Ch. Cambridge).

31For Charlestown’s role in New England’s burgeoning merchant

culture, see Bailyn, Merchants in the Seventeenth Century, 96.

32For the Lamson family’s Atlantic reach, see David R. Mould and Missy

Loewe, Historic Gravestone Art of Charleston, South Carolina,

1695–1802 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.,

2006), 30, 35–36, 39, 42, 63–65, 69, 72–73, 209–12.

To date I can find no direct evidence of whether the Lamson family employed

enslaved labor in their shop, but for an example of an enslaved artisan from